Speeding up your code by mirroring the CPU

What if I told you your code was primarily waiting for things to happen, rather than doing stuff? Waiting is exactly what happens when you attempt to interact with any component of your system that is a peripheral, so that's your network, the disk, anything you have connected via USB, Firewire or Thunderbolt. In this article I'm going to talk about how to do other stuff while you're waiting, to better use the resources available to you, so you can squeeze out the next 100 users from your hardware.

In order to do this I'm going to first talk about the observer pattern.

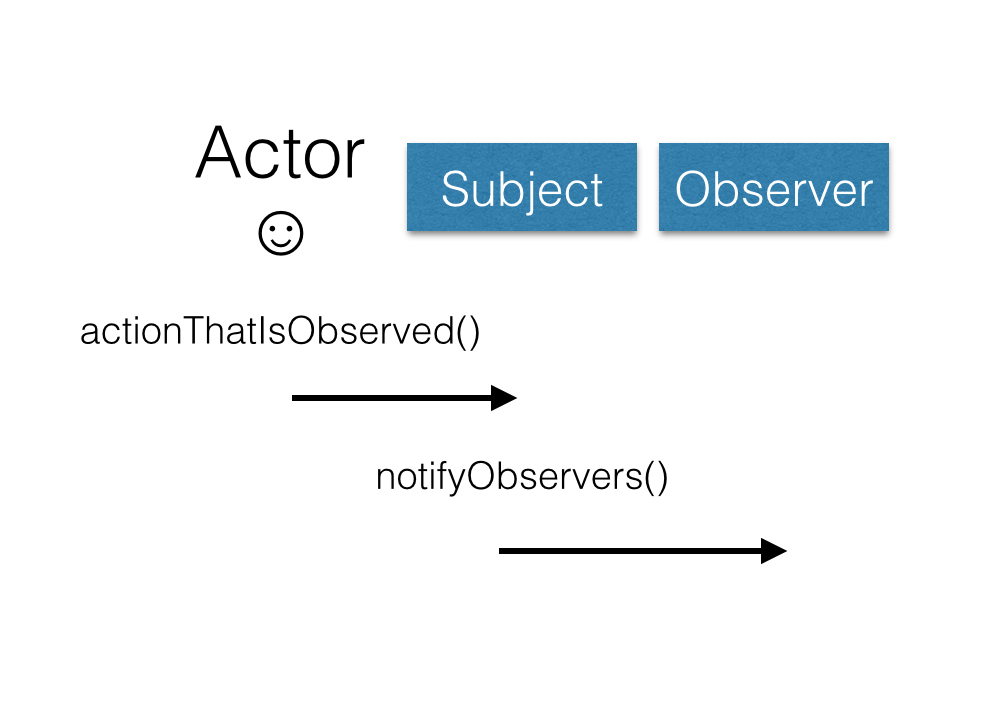

The observer pattern is a design pattern that is implemented in many libraries. It consists of 2 components, the observer and the subject. The subject is aware of all of the observers that are interested in a specific thing happening, and will call a method on each of them when the thing that the observers are interested in happens.

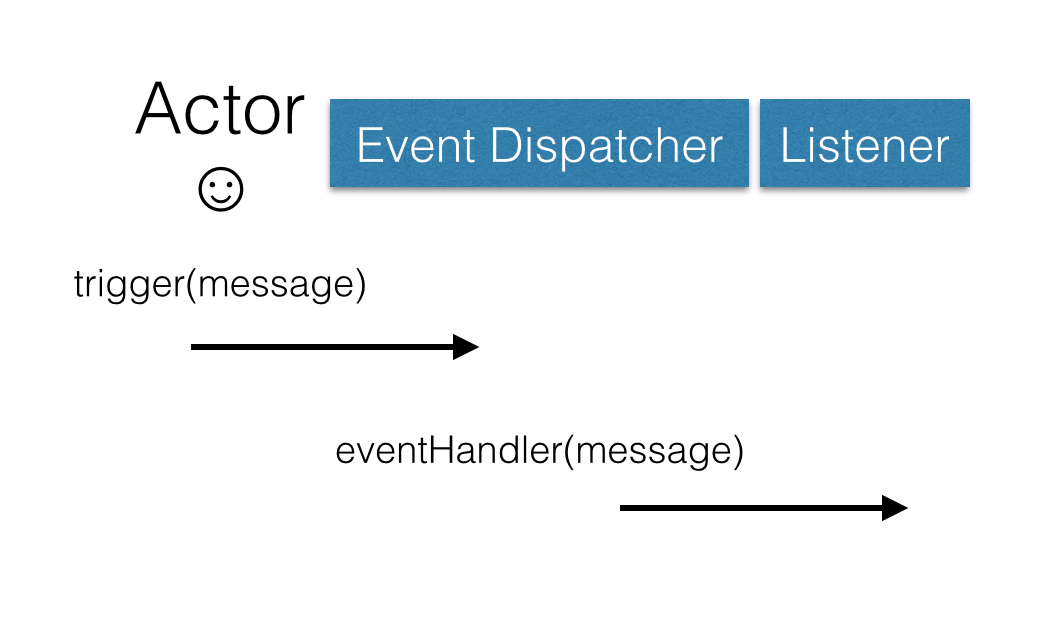

A popular implementation of the observer pattern is the Event Dispatcher (like Symfony's). This is a common implementation in which the subject is a the event dispatcher, and the listeners that are executed when certain events are triggered in the dispatcher are the observers.

The observer pattern is exactly what happens internally inside your computer, when you want to interact with a peripheral. You register your interest in being notified when an event happens, such as writing to disk, or a packet coming in from the network, by setting an interrupt on the CPU. Interrupts are triggered when that event occurs and your code is run, it does this by interrupting the code that is currently scheduled to run on the CPU at that time, and by running your code instead - hence the name.

This is exactly the same as the observer pattern. Our CPU is the subject, and our code is the observer that is triggered when the interrupt happens.

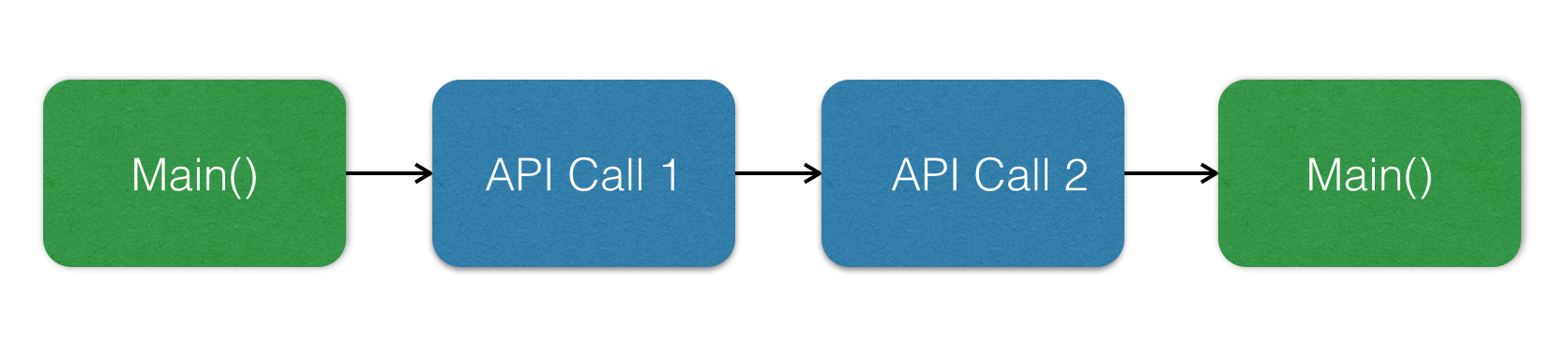

Now there are two ways of dealing with this situation. The first is to simply wait for our interrupt to be called before doing anything else. This is the easiest to understand because you're simply doing one thing after another. However it's inefficient because you're constantly waiting.

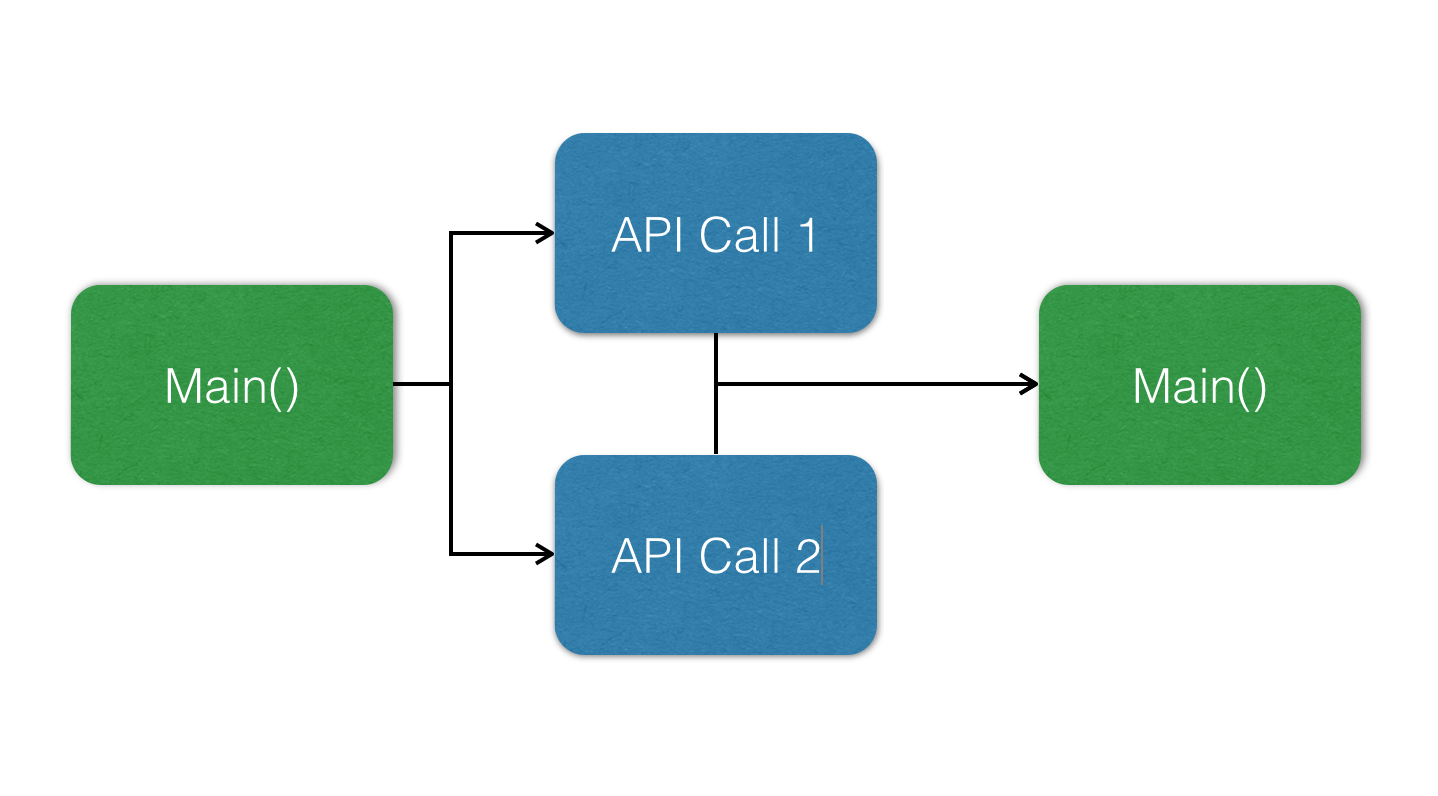

The second way is a lot more efficient. That is to pass a piece of code to be executed at time the Listener is called, but keep doing other things until that point. That way we take advantage of the CPU we would have otherwise sitting idle.

This is called a non-blocking architecture. This is because we don't block any other code from running while we're waiting. There are languages that explicitly support non-blocking code, including, Python, Java, Go, Rust, JavaScript, or Ruby.

Non-blocking systems are fast. However they're also hard to understand, because any observer can run at any time, it's often difficult to determine which bits of memory are being read from, or written to. This can lead to complex to debug race conditions.

To make it simpler, we can regiment our architecture with an event dispatcher. An Event dispatcher is a subject that takes messages, and based on the content of these messages, trigger different observers, which when combined with an Event Dispatcher call listeners. An example of one of these messages would be "file read finished", combined with the content of the file.

This reduces the opportunity for race conditions because the only shared memory is the message, and we can make that immutable (read only), as once passed to the listener, the listener can simply make a new message to communicate with other listeners.

However inside our system we don't only want to do low level things. We frequently want to combine a number of low level tasks into a single unit. To this end we can also use an event dispatcher to trigger a more abstract event, such as "user signed up", allowing us to have the efficiency of low level non-blocking code, for our high level business logic.

Taking a further step back, once we decide that all these listeners only communicate via a single message, we can split these listeners up onto different machines, and communicate via the network. Typically we'd do this via a queue server, and clients for it. This allows us to not only make our system more scalable and resilient as we can add more machines to it, but also language agnostic, allowing us to choose the right language for the task listener is completing.

Over the next few articles I'm going to be exploring how to develop these message passing systems in more detail, starting with structuring command, protecting your infrastructure from complex errors, moving on to utilizing customized front-end caches to speed up your code, then on to how to make your system resilient and scalable with event sourcing, and finally wrapping up with combining them all in CQRS.